Welcome to Think Out Loud, a newsletter about technology and philosophy. If you’d like to learn more about this substack, you can do so here. You can also subscribe below:

Contents

Camus and COVID-19

What I’ve been reading recently

2.1 Cryptocurrency

2.2 Philosophy

2.3 Data science and machine learning

2.4 Marketing

2.5 Solo-entrepreneurship

2.6 Politics

1. Camus and COVID-19

Note: No spoilers are below!

The Plague, set in the 1940s, is the (fictitious) story of the city of Oran during an outbreak of bubonic plague. The story is stitched together by a mysterious narrator based on his personal experience, as well as journals and anecdotes from those around him. The plot, as is typical in Albert Camus’ writing, serves to point out the contradictory actions humans take as we struggle to create meaning in a world that is out of our control.

Camus did not consider himself a philosopher, due to his skepticism of systematic thought. In this sense, he can almost be seen as being early to postmodernism. Instead, Camus preferred the label “Artist” to “Philosopher”. I’d like to respect Camus in his refusal to be labeled a philosopher, but I can’t. Camus may not be trying to system build in the way typical philosophers do, but, through his stance on meaninglessness, Camus still gives us heuristics we can live by that are highly philosophical.

This might sound bizarre if you haven’t read Camus before. Meaninglessness might seem, by definition, the single most uninspiring conclusion one could draw from a piece of art. But it’s really the opposite. Instead of leaving the reader with a sense of hopelessness, Camus trades emphasis on things like organized religion and abstract philosophies for attention to the here and now. Without spoiling anything, I can also say that the main characters in The Plague demonstrate the need for this change in prioritization.

Much of what has happened during COVID has mirrored what Camus wrote 74 years back. Like the characters in The Plague, everyone during COVID has done some amount of reflection on the ways they might live differently going forward. However, it seems like most of the reflection we’ve done the last year has been ideological. That ideological lens is exactly what Camus warns us of. If there’s one lesson from The Plague that seems relevant today, it’s that we can’t live our lives as slaves to abstractions; political, philosophical, or otherwise. This doesn’t mean we all sit down in a big drum circle and have a sing along. Instead, we should remember to give other people—especially those we love—the time, attention, and respect they deserve. Even when we disagree with them.

2. What I’ve been reading recently

2.1 Cryptocurrency

The Bitcoin Dream is Dead - A relatively basic article on how vision of Bitcoin changed from a currency to a store of value (like gold). It might be a good introduction for those unfamiliar with the topic, but fails to dive into details like the lightning network for “digital cash”.

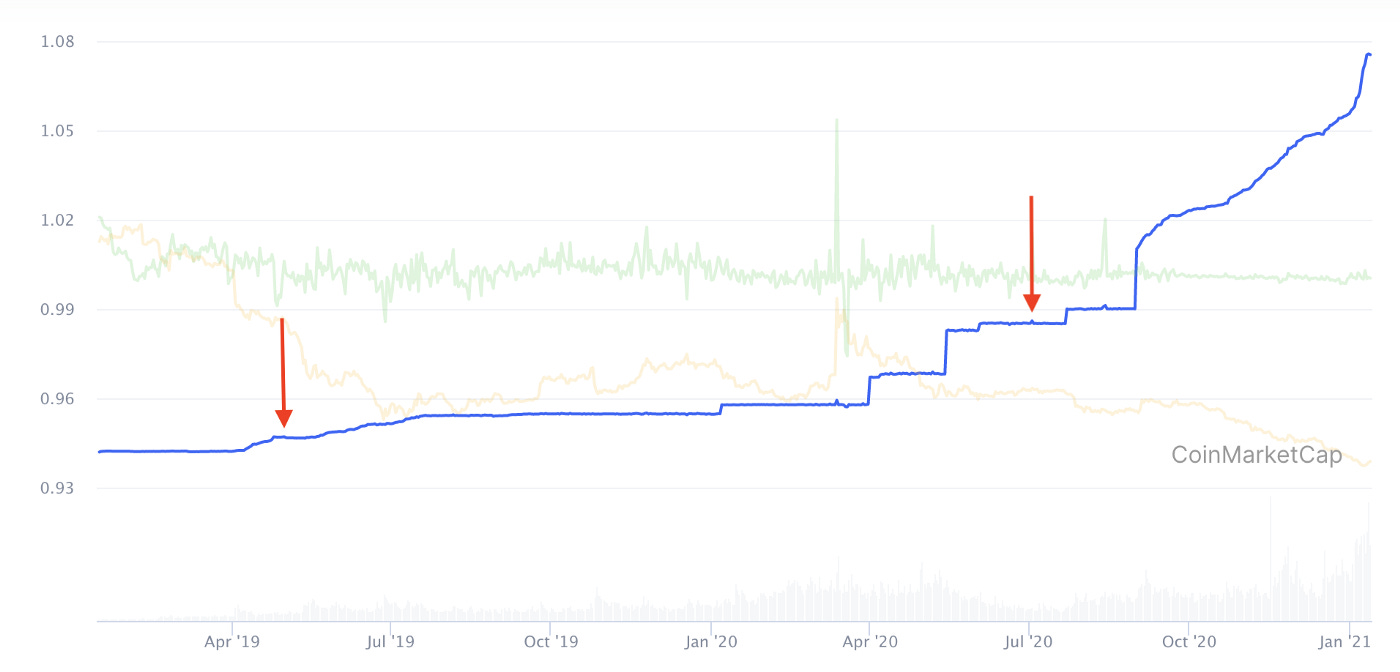

The Bit Short: Inside Crypto’s Doomsday Machine - This is an important article for those speculating on Bitcoin. If you haven’t been already following articles on Tether over the past few years, the gist is that unbanked (and unregulated) crypto exchanges are promoting leveraged trading for Bitcoins using Tether. Tether is supposed to be tied to dollars that Tether, according to this article and others, do not have. The short version of this argument is that Tether is effectively printing its own money to fleece Bitcoiners for their USD, and it’s propping up Bitcoin prices along the way.

If you’re not familiar with this problem, the part of the article summarizes it well (my parentheses):

1. Bob, a crypto investor, puts $100 of real US dollars into Coinbase (a reliable exchange).

2. Bob then uses those dollars to buy $100 worth of Bitcoin on Coinbase.

3. Bob transfers his $100 in Bitcoin to an unbanked exchange, like Bybit (unbanked exchange).

4. Bob begins trading crypto on Bybit, using leverage (borrowed Tether, up to 100x greater than Bob’s banked Bitcoin), and receiving promotional giveaways — all of which are Tether-denominated.

5. Tether Ltd. buys Bob’s Bitcoins from him on the exchange, almost certainly through a deniable proxy trading account. Bob gets paid in Tethers.

6. Tether Ltd. takes Bob’s Bitcoins and moves them onto a banked exchange like Coinbase.

7. Finally, Tether Ltd. sells Bob’s Bitcoins on Coinbase for dollars, and exits the crypto markets.

I’d actually already been informed of the Tether bubble propping up Bitcoin several times by friends of mine working in the crypto/blockchain space back in 2018, but the problem seems to have exacerbated dramatically in recent months. In all honesty, when I’d written my previous newsletter on Bitcoin, I’d completely forgotten about Tether. I didn’t think it could be the cause of the insane market we’ve seen, as I wasn’t sure of the volume of Tether transactions. But, if the graphs in this post are to be trusted, Tether very well could be the cause of the recent boom.

Tethers issued

Bitcoin’s price

The final piece that makes this article convincing is this:

“Tether Ltd.’s bank is Deltec bank in the Bahamas, and the Bahamas discloses how much foreign currency its domestic banks hold each month.

…

From January 2020 to September 2020, the amount of all foreign currencies held by all the domestic banks in the Bahamas increases by only $600 million — going from $4.7B to $5.3B.

But during the same period, total issued Tethers increased by almost $5.4 billion — going from $4.6B to $10B!”

Some closing thoughts:

I’m not saying this case is bulletproof. There are definitely alternative explanations to this price behavior. But this should still make people in Bitcoin purely for speculation nervous.

“True” Bitcoin advocates shouldn’t care about fluctuations in Bitcoin’s price relative to USD. If 2/3 of the recent market are really Tether, and it blows up, we’ll see how many people decide not to cash out under flattened demand.

2.2 Philosophy

The Plague (Albert Camus) - I might be somewhat biased because I’m reading this during a pandemic, but I loved this book.

Moral Competence - The intention vs. results debate in ethics is about as fundamental as arguments in applied ethics get. The author—a startup founder—touches on the challenges they experienced starting a company with the intention of doing good, and failing. I’ve seen a number of people—including people close to me—do the same thing, and, like the author, not end up seeing results. This is tougher to hear about than just a normal business failure, because it’s a failure on two fronts:

The moral front: Could your time have been spent doing more good?

The career front: Could I have advanced my career further had I not spent time on it?

I’m skeptical of the institution of trying to start a company on the basis of moral good. Moral good and profit motive—even if that the profit motive is just to employ the people in your company—seem at odds with one another. Companies take on lives of their own, and, while it’s still important to reign them in when they’re going down the wrong path (morally and financially) mixing intentions between the profit motive and moral motive seems to cause a failing on both fronts.

“What we were missing, and what many social-good founders are missing, is moral competence.

…

The morally incompetent want purpose; they want to be on the front-lines of the helping. But for the morally incompetent, helping people is more important than the folks being helped. They don't offer service, they seek it. The service outranks the outcome.”

Noubar Afeyan on the Permission to Leap (Ep. 113) - This one is a podcast with a Co-founder of Moderna, the biotech company responsible for one of the leading COVID vaccines. Some of the conversation around recent innovations in the biotech space was interesting, but Afeyan’s comments on academia were what really resonated with me. Lately I find that most of the scientific breakthroughs that interest me are born out of industry, not academia. Many people, like Moderna’s cofounder, attribute that to some of the bizarre incentives related to publishing in academia today.

COWEN: “As you well know, some of the early papers on mRNA vaccines — they were rejected repeatedly at academic journals. Katalin Karikó had trouble in her academic career. Now she’s highly likely to win a Nobel Prize. What’s wrong with academia? And how do we fix it?”

AFEYAN: “I’ll just say, Tyler, that is true generally. In their particular case, it was really more about pretty basic mRNA modifications as opposed to vaccines because back 20 years ago, people weren’t working on vaccines. They were just working on being able to show that mRNA could even get into a human cell. People were quite resistant to believing that was possible.

Look, the scientific method, the scientific community — it works on advances that are predicated on current and prior advances. Incremental advances are the coin of the realm. It’s not that they’re conservative. It’s just that the process, the communal process of accepting truth as that which can’t be negated, causes you to therefore be, in every which way, questioning everything.

I learned long ago the expression organized skepticism. That’s what science is predicated on. As a result, if you come forward with something that is not fully supported by and connected to the current reality, people don’t know what to do with it. What many academic scientists do is to spend the next 5, 10 years putting the connections in place to make what’s being proposed a natural extension of what existed before.

In industry, we don’t have that need, and the reason Moderna was able to really be the pioneer in the space of establishing a therapeutic platform, even before a vaccine platform, is because for us, the lack of connection between what we were able to do and what had been done before was marginally interesting, but we weren’t trying to publish it.

When you patent something, you don’t have to show that it’s a natural extension of what people did. You just have to describe something that is novel, that is unobvious. In fact, the less connected, the more unobvious, and/or the less connectible.

My answer to your question would be, a lot of it has to do with the essence of academic, scientific pursuit of knowledge, which causes this collectivism, and it has its disadvantages. One of them is, if you don’t have all the pieces together, people will be skeptical.”

To me, this is one of the most important problems facing society today. Science needs a home; somewhere scientists can be creative, outside of industry, or academia (in its present form). The opportunity cost of not having this kind of space seem, to me, too high to ignore.

Trolling, Basedness, Virtue, and Vitalism - A brief essay on building up ethics in the age of internet culture and postmodernism. The article tacitly presupposes some familiarity with Deleuze, so I wouldn’t recommend it for those who aren’t familiar with his terminology. I’ve read some Deleuze a few years back (with the assistance of someone that based his Ph.D on Deleuze’s work) and I still always find myself looking everything up when I read anything related to Deleuze. I’ll probably have to look back into Deleuze, then come back to this article.

If you’re interested in learning about Deleuze and you happen to live in Seattle, I would recommend joining the Seattle Analytic philosophy club.

2.3 Data Science and Machine Learning

ML Ops: Data Science Version Control - An excellent jumping-off point for versioning machine learning projects. I’m with a small team to start our machine learning efforts at Attentive, so I’ve been reading into these topics. P.S - we’re hiring!

How to Version Control your Machine Learning task — 1 and 2- Another 2 pieces I read on versioning for ML projects. These covers DVC (Data Version Control) a popular tool for versioning machine learning projects.

Lifetimes - “Measuring users is hard. Lifetimes makes it easy” is the motto of Lifetimes, and it holds true. Lifetimes is a straightforward library for predicting all kinds of handy e-commerce style metrics, some examples, from the repo, are below:

Predicting how often a visitor will return to your website

Understanding how frequently a patient may return to a hospital

Predicting individuals who have churned from an app using only their usage history

Predicting repeat purchases from a customer

Predicting the lifetime value of your customers

2.4 Marketing

How a Small Business Used TikTok Influencers to Drive $500k a Month in Sales - This was was a small peanut butter side hustle that used TikTok influencers to expand their business (with dramatic success!) Plenty of brands have had breakthrough success via Instagram; TikTok shaping up to be as good a channel.

Peter Fader, Wharton (on custom lifetime value) - Much of my work lately is applying data engineering and data science techniques to marketing problems. This is a talk from a Wharton professor going over basics the some of the models used in the “lifetimes” package I talk about in the “Data science” section, popularized by shopify.

The underlying idea behind the model is that everyone has an unobserved purchasing rate that can be utilized to forecast custom lifetime value with some relatively simple calculations. No Russian P.hDs required. Maybe this is basic for folks familiar with the space, but, as someone new to marketing concepts, it was very useful for me to understand what I’m working with. The talk is wonderful: Fader is straight to the point, and I learned a lot.

2.5 Solo-entrepreneurship

I quit my tech job, here’s what I learned - The author goes over a brief list of things she found surprising leaving her product management job to independently run her solo-entrepreneurship projects. She emphasizes a couple of major points:

The illusion of thinking that working at small companies will teach you to run a business independently

The difficulties of branding for those used to working for companies

A certain flavor of stoicism (though she doesn’t put it that way)

“You can also experiment venturing into the wilderness [independence from employment] at some point. At best, you learn new survival skills and maybe even rewrite your baseline happiness. At worst, you gain a deeper appreciation for your cross-functional partners, and the luxury of life in a cozy simulator [your job].”

Worth a read if you like following solo-preneurs. You should also follow this guy, Takuya; he’s the solo-dev building my favorite notetaking app, Inkdrop.

2.6 Politics

The Big Lie Destroying American Democracy - The author argues, simply, that Trump and the 147 members of congress that voted against accepting the election results must admit wrongdoing before we’ll see any progress mending the divide in the country. The article cites several other cases where an open admission of wrongdoing—or lack thereof—was the key factor in changing public opinion, including the South African Apartheid and Nazi Germany. Evidence can’t convince the public otherwise, only testimony.